Opening sentence of the abstract in the peer-reviewed paper “When Meat Gets Personal, Animals’ Minds Matter Less: Motivated Use of Intelligence Information in Judgments of Moral Standing” in Social Psychological and Personality Science by Jared Piazza and Steve Loughnan: “Why are many Westerners outraged by dog meat, but comfortable with pork?”

The single-word answer which explains everything—bacon—never occurs to the authors.

Neither does the well known truth that dogs bite back when chased (pigs can be nasty, too). I’ve eaten both animals and I know. Pig is more versatile. Everything from chops to the loin is juicy and delicious—where would we be without pickled pigs feet?—whereas dog has fewer choice cuts and is generally stringy or greasy. And don’t even get me started on sausage, though some dogs do resemble walking sausages.

Dog as food is still found in parts of the world. If this article is right “China, Indonesia, Korea, Mexico, Philippines, Polynesia, Taiwan, Vietnam, the Arctic and Antarctic and two cantons in Switzerland” still serve up barking burgers. (I had a dog taco in Mexico, you racist.)

But maybe bacon isn’t the answer after all. Fetching a dog bone is (as many article say) taboo in the enlightened cities of the West (I say cities), and when the media reports on dog-as-chow there is usually what is termed a flap.

Before venturing into the paper, why would you say there is this excitement? Custom, say I. We’re long used to eating pigs and have for just as long and maybe longer valued dogs as companions. We consider it rude to eat companions. Whereas we’re fine with slicing and dicing an animal kept in a pen far from eyes and fattened for feasting. Plus you can’t entirely discount bacon. Call this the commonsense, or Custom answer. Now let’s see what our authors say.

It’s Piazza and Loughnan’s theory that our dinners’ intelligence should be the driving factor in drawing lines between what’s acceptable and taboo, figuring it’s fine to chew less intelligent animals and eschew more intelligent ones. Yet

people will actively disregard intelligence information when considering the moral standing of certain animals that pose a moral challenge to the consumer. That is, while evidence for an animal’s mind is generally persuasive, it is not compelling when a person is motivated to defend their use of the animal as food.

Piazza and Loughnan don’t appear aware that many people know that people are people and not animals, in the sense that people are rational creatures and animals not. This is why “Rise, Peter; kill, and eat” makes (made) sense to most of us. Considering a beast’s “intelligence” is a recent phenomenon, constrained to Westerners who have forgotten the distinction between men and animals.

Anyway, our duo took to the internet and asked 58 people to “imagine that in the distant future, scientists went on an expedition to another planet and discovered a new species called the ‘trablans.'” Half the people were told the trablans were intelligent, half not, and they were then asked questions like “Is it OK to start eating the trablans?”. Lo, a few more of the folks who were told the trablans were dumb said yes than did the people who were told the trablans were intelligent. A wee p-value “confirmed” the difference was in fact a difference.

Two other sets of people and questions were asked with similar results.

Imagine the faux pas of you leading a team of scientists to a distant planet where you end up serving what turns out to be the native rational trablans for supper. No such embarrassment need happen if trablans are mere animals.

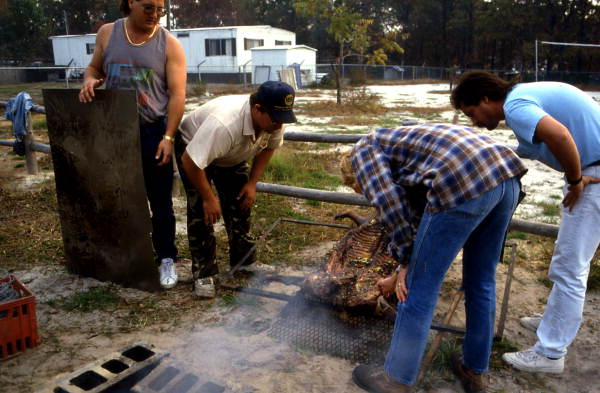

So there is a test: do the trablans possess a rational nature like humans, or are they mere beasts? If the latter, fire up the coals and ice the beer. If the former, they are really like us whatever they look like, and cannibalism, though at times and places accepted, is against natural law.

That “times and places” is key, incidentally. If you argue against natural law, how many people and in how many places have to act a certain way to make that way “right” or “moral”? One? A thousand? Must they all live contiguously, or is geographic separation allowable? Without delving into it, it’s easy to see that the only consistent solution is natural law.

Let’s let the authors have their final word: “Smart animals deserve our moral concern, unless, of course,

we want to eat them.”