The ghost in the machine, we learn, is an old fallacy.

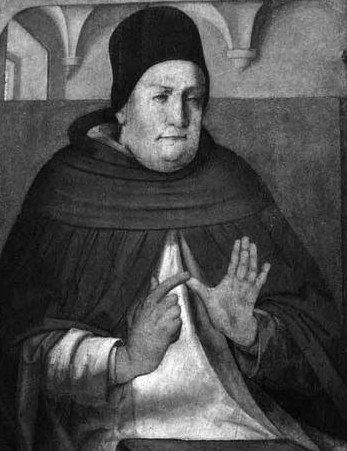

Chapter 57 The opinion of Plato concerning the union of the intellectual soul with the body (alternate translation)

1 MOVED by these and like reasons some have asserted that no intellectual substance can be the form of a body. But since man’s very nature seemed to controvert this opinion, in that he appears to be composed of intellectual soul and body, they devised certain solutions so as to save the nature of man.

2 Accordingly, Plato and his school held that the intellectual soul is not united to the body as form to matter, but only as mover to movable, for he said that the soul is in the body as a sailor in a boat. In this way the union of soul and body would only be by virtual contact, of which we have spoken above. But this would seem inadmissible. For according to the contact in question, there does not result one thing simply, as we have proved: whereas from the union of soul and body there results a man. It follows then that a man is not one simply, and neither consequently a being simply, but accidentally.

Notes Ghost in the machine is an old problem! But it’s more of an evocative metaphor than sailor-in-a-boat.

3 In order to avoid this Plato said that a man is not a thing composed of soul and body, but that the soul itself using a body is a man: thus Peter is not a thing composed of man and clothes, but a man using clothes.

4 But this is shown to be impossible. For animal and man are sensible and natural things. But this would not be the case if the body and its parts were not of the essence of man and animal, and the soul were the whole essence of both, as the aforesaid opinion holds: for the soul is neither a sensible nor a material thing. Consequently it is impossible for man and animal to be a soul using a body, and not a thing composed of body and soul.

Notes The soul is the form of the body, as Aquinas points out again and again. Our intellects are not material, it’s true, but our intellects are part of our form. The fallacy of ghost in the machine nowadays arises, I think, because people falsely discredit the non-material, i.e. the supernatural.

5 Again. It is impossible that there be one operation of things diverse in being. And in speaking of an operation being one, I refer not to that in which the action terminates, but to the manner in which it proceeds from the agent:–for many persons rowing one boat make one action on the part of the thing done, which is one, but on the part of the rowers there are many actions, for there are many strokes of the oar,–because, since action is consequent upon form and power, it follows that things differing in forms and powers differ in action.

Now, though the soul has a proper operation, wherein the body has no share, namely intelligence, there are nevertheless certain operations common to it and the body, such as fear, anger, sensation, and so forth; for these happen by reason of a certain transmutation in a determinate part of the body, which proves that they are operations of the soul and body together. Therefore from the soul and body there must result one thing, and they have not each a distinct being.

Notes So much is easy to see. The remainder of this chapter is Aquinas examining Plato’s attempt at evading the force of paragraph 5. There are some interesting bits, but it can be skipped. Dog lovers might enjoy paragraph 8—and then not.

6 According to the opinion of Plato this argument may be rebutted. For it is not impossible for mover and moved, though different in being, to have the same act: because the same act belongs to the mover as wherefrom it is, and to the moved as wherein it is. Wherefore Plato held that the aforesaid operations are common to the soul and body, so that, to wit, they are the soul’s as mover, and the body’s as moved.

7 But this cannot be. For as the Philosopher proves in 2 De Anima, sensation results from our being moved by exterior sensibles. Wherefore a man cannot sense without an exterior sensible, just as a thing cannot be moved without a mover. Consequently the organ of sense is moved and passive in sensing, but this is owing to the external sensible. And that whereby it is passive is the sense: which is proved by the fact that things devoid of sense are not passive to sensibles by the same kind of passion. Therefore sense is the passive power of the organ. Consequently the sensitive soul is not as mover and agent in sensing, but as that whereby the patient is passive. And this cannot have a distinct being from the patient. Therefore the sensitive soul has not a distinct being from the animate body.

8 Further. Although movement is the common act of mover and moved, yet it is one operation to cause movement and another to receive movement; hence we have two predicaments, action and passion. Accordingly, if in sensing the sensitive soul is in the position of agent, and the body in that of patient, the operation of the soul will be other than the operation of the body. Consequently the sensitive soul will have an operation proper to it: and therefore it will have its proper subsistence. Hence when the body is destroyed it will not cease to exist. Therefore sensitive souls even of irrational animals will be immortal: which seems improbable. And yet it is not out of keeping with Plato’s opinion. But there will be a place for inquiring into this further on.

9 Moreover. The movable does not derive its species from its mover. Consequently if the soul is not united to the body except as mover to movable, the body and its parts do not take their species from the soul. Wherefore at the soul’s departure, the body and its parts will remain of the same species. Yet this is clearly false: for flesh, bone, hands, and like parts, after the soul’s departure, are so called only equivocally, since none of these parts retains its proper operation that results from the species. Therefore the soul is not united to the body merely as mover to movable, or as man to his clothes.

Notes A dead man is no longer a man, merely decaying flesh. A lump of tissue, as those keen on killing the young might say.

10 Further. The movable has not being through its mover, but only movement. Consequently if the soul be united to the body merely as its mover, the body will indeed be moved by the soul, but will not have being through it. But in the living thing to live is to be. Therefore the body would not live through the soul.

11 Again. The movable is neither generated through the mover’s application to it nor corrupted by being separated from it, since the movable depends not on the mover for its being, but only in the point of being moved. If then the soul be united to the body merely as its mover, it will follow that neither in the union of soul and body will there be generation, nor corruption in their separation. And thus death which consists in the separation of soul and body will not be the corruption of an animal: which is clearly false.

12 Further. Every self-mover is such that it is in it to be moved and not to be moved, to move and not to move. Now the soul, according to Plato’s opinion, moves the body as a self-mover. Consequently it is in the soul’s power to move the body and not to move it. Wherefore if it be united to it merely as mover to movable, it will be in the soul’s power to be separated from the body at will, and to be reunited to it at will: which is clearly false.

Notes So much for astral projection.

13 That the soul is united to the body as its proper form, is proved thus. That whereby a thing from being potentially is made an actual being, is its form and act. Now the body is made by the soul an actual being from existing potentially: since to live is the being of a living thing. But the seed before animation is only a living thing in potentiality, and is made an actually living thing by the soul. Therefore the soul is the form of the animated body.

14 Moreover. Since both being and operation belong neither to the form alone, nor to the matter alone, but to the composite, being and action are ascribed to two things, one of which is to the other as form to matter; for we say that a man is healthy in body and in health, and that he is knowing in knowledge and in his soul, wherein knowledge is a form of the soul knowing, and health of the healthy body. Now to live and to sense are ascribed to both soul and body: for we are said to live and sense both in soul and body: but by the soul as by the principle of life and sensation. Therefore the soul is the form of the body.

15 Further. The whole sensitive soul has to the whole body the same relation as part to part. Now part is to part in such a way that it is its form and act, for sight is the form and act of the eye. Therefore the soul is the form and act of the body.