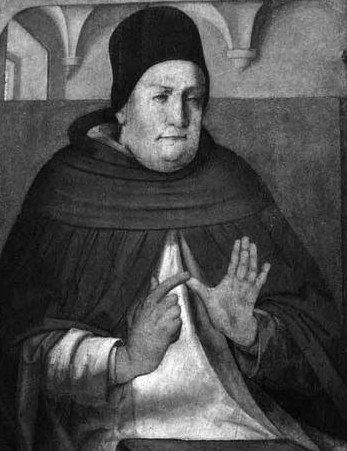

Clik here to view.

This may be proved in three ways. The first…

We’re deep into technicalities this week, all of which reinforce the proof that God is the first cause of all. As we have long learned, Thomas was nothing if not thorough.

Chapter 41 That the distinction of things is not on account of a contrariety of agents (alternate translation)

1 FROM the above we may also prove that the cause of distinction among things is not a diversity or even a contrariety of agents.

2 For if the diverse agents who cause the diversity among things, are ordered to one another, there must be some cause of this order: since many are not united together save by some one. And thus the principle of this order will be the first and sole cause of the distinction of things. If, on the other hand, these various agents are not ordered to one another, their convergence to the effect of producing the diversity of things will be accidental: wherefore the distinction of things will be by chance; the contrary of which has been proved above.

Notes And recall, as always, chance is not ontic.

3 Again. Ordered effects do not proceed from diverse causes having no order, except perhaps accidentally, for diverse things as such do not produce one. Now things mutually distinct are found to have a mutual order, and this not by chance: since for the most part one is helped by another. Wherefore it is impossible that the distinction among things thus ordered, be on account of a diversity of agents without order.

Notes In other words, there is such a thing as coincidence.

4 Moreover. Things that have a cause of their distinction cannot be the first cause of the distinction of things. Now, if we take several co-ordinate agents, they must needs have a cause of their distinction: because they have a cause of their being, since all beings are from one first being, as was shown above; and the cause of a thing’s being is the same as the cause of its distinction from others, as we have proved. Therefore diversity of agents cannot be the first cause of distinction among things.

5 Again. If the diversity of things comes of the diversity or contrariety of various agents, this would seem especially to apply, as many maintain, to the contrariety of good and evil, so that all good things proceed from a good principle, and evil things from an evil principle: for good and evil are in every genus.

But there cannot be one first principle of all evil things. For, since those things that are through another, are reduced to those that are of themselves, it would follow that the first active cause of evils is evil of itself. Now a thing is said to be such of itself, if it is such by its essence. Therefore its essence will not be good. But this is impossible. For everything that is, must of necessity be good in so far as it is a being; because everything loves its being and desires it to be preserved; a sign of which is that everything resists its own corruption; and good is what all desire. Therefore distinction among things cannot proceed from two contrary principles, the one good, and the other evil.

Notes Life is not a battle between Good and Evil. It is a battle to avoid corruption. Plus, don’t forget that here and below, evil is a privation, an absence.

6 Further. Every agent acts in as much as it is actual; and in as much as it is in act, everything is perfect: and everything that is perfect, as such, is said to be good. Therefore every agent, as such, is good. Wherefore if a thing is essentially evil, it cannot be an agent. But if it is the first principle of evils, it must be essentially evil, as we have proved. Therefore it is impossible that the distinction among things proceed from two principles, good and evil.

7 Moreover. If every being, as such, is good, it follows that evil, as such, is a non-being. Now, no efficient cause can be assigned to non-being, as such, since every agent acts for as much as it is an actual being, and every agent produces its like. Therefore no per se efficient cause can be assigned to evil, as such. Therefore evils cannot be reduced to one first cause that is of itself the cause of all evils.

8 Further. That which results beside the intention of the agent, has no per se cause, but befalls accidentally: for instance when a man finds a treasure while digging to plant. Now evil cannot result in an effect except beside the intention of the agent, for every agent intends a good, since the good is what all desire. Therefore evil has not a per se cause, but befalls accidentally in the effects of causes. Therefore we cannot assign one first principle to all evils.

Notes Keep in mind what is happening here. When a man sins he thinks, at the moment, the sin is a good. And you have to love the example of finding treasure when burrowing for potatoes!

9 Further. Contrary agents have contrary actions. Therefore we must not assign contrary principles to things that result from one action. Now good and evil are produced by the same action: thus by the same action water is corrupted and air generated. Therefore the difference of good and evil that we find in things is no reason for affirming contrary principles.

10 Moreover. That which altogether is not, is neither good nor evil. Now that which is, for as much as it is, is good, as proved above. Therefore a thing is evil forasmuch as it is a non-being. But this is a being with a privation. Wherefore evil as such is a being with a privation, and the evil itself is this very privation. Now privation has no per se efficient cause: since every agent acts inasmuch as it has a form: wherefore the per se effect of an agent must be something having that form, because an agent produces its like, except accidentally. It follows, then, that evil has no per se efficient cause, but befalls accidentally in the effects of causes which are effective per se.

11 Consequently there is not one per se principle of evil: but the first principle of all things is one first good, in whose effects evil is an accidental consequence.

Notes Intending evil for another isn’t what is meant, because that act is, by the agent, at least at the moment, seen as a good. Though it isn’t here argued, that this is so means the definition of what is truly good and evil must come from outside desire.