Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Physicians long ago abandoned the Hippocratic Oath, for at least the reason that its call for physicians not to cause harm went against the modern acceptance, and even boasting, of killing. Which is to say, abortion and suicide, assisted other otherwise, were not countenanced in the old oath, but they are well loved today.

But harm doesn’t include only death. What about those physicians, or rather medical professionals, who maim women for religious reasons? And what about those knife wielders who, for example, chop off various useful or otherwise healthy body parts of patients by patient request?

And what about those associated with medicine who give clean needles to heroin users? The argument for this largess is that heroin users, were they to use dirty needles, are apt to contract hepatitis or some other disease; therefore, the clean needles (when they are used) will stop infections.

The argument is valid: if dirty needles carry disease and clean ones don’t, supplying clean ones will cause a reduction in disease rate (naturally, heroin users won’t always, in the hunger of the moment, use the new needles). And this has been seen.

But it is also so that the clean needles will encourage folks to take heroin, or other drugs, and that heroin causes harm, and that when under the influence of heroin (and other drugs) harm is often caused to the user and others. So the physician, while creating a barricade for one harm, clears the path for others. How can we calculate the total harms, with and without clean needle programs?

Enter the peer-reviewed paper “Should healthcare professionals sometimes allow harm? The case of self-injury” by Patrick J Sullivan in the Journal of Medical Ethics.

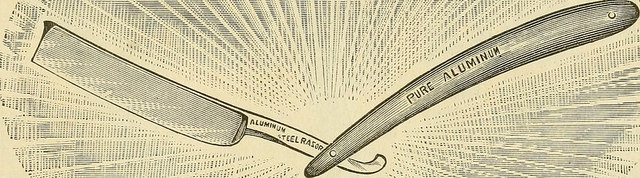

This is being talked of as the “clean razor” paper, because Sullivan would supply clean razors to the (mainly) women who habitually cut themselves. The paradigm case:

Alison is 35 years old and has a long history of mental health problems. As a teenager, Alison started to cut herself and this has continued. In conversation Alison describes how she started to self-injure almost by accident and found that it made her feel better. Her self-injury follows a particular pattern and she becomes anxious and distressed if prevented from acting in this way. She describes wanting to stop and understands that there are better ways of coping but at the moment cutting is her preferred means of dealing with feelings of distress…

The proposed solution:

Rather than trying to stop Alison cutting herself the clinical team has agreed that she be able to access clean razors for her own use and that staff should work with her to help her understand how to injure herself more safely.

Nick the wrong blood vessel, and you bleed out. Use a dirty razor and open yourself (a bad pun?) to all kinds of diseases. Give Alison clean needles and a copy of Gray’s Anatomy and her opportunities for contracting diseases are lessened (but not eliminated), as are her chances of cutting the wrong thing at the wrong time.

Since she is being supplied by what she wants, in equipment and guidance, she might be encouraged to continue slicing herself open. Perhaps at a higher frequency than when she was doing it the old fashioned way. And if she cuts herself more often, she increases the opportunities for disease and death.

Objections? Sullivan considers, “It could be objected here, that self-injury is not an autonomous choice and therefore the decision to engage in such behaviour should not be respected, even less valued.” But this cannot be so, since it is by free will that self-injury occurs. How about plain counseling? Doesn’t work, he says.

…Furthermore, even if the choice to self injure were not autonomous, their [sic] still remain moral and clinical questions about the means used to prevent such behavior. Enforced interventions are often ineffective and are certainly perceived negatively.

Significant infringements on basic freedoms are likely to produce a confrontational rather than therapeutic environment that increases levels of distress and reduces the chance of a positive outcome in the longer term. In such circumstances attempts to take away someone’s ability to self-injure reduce their coping options and are likely to increase their distress or increase the risk of harm. For example, it must be noted that many individuals who self-injure have a history of abuse or trauma and preventative measures may increase their feelings of powerlessness and in extreme cases result in additional trauma and therapeutic alienation.

All of this is highly disputable, especially given the statistical nature of the claims. However, we’ll forgo those criticism here to concentrate of the “pro self-harm” arguments.

Sullivan says, “Self-injury is being allowed, in order to maintain its role as a coping mechanism, based on the understanding that this occurs safety [sic].” It isn’t occurring safely, a major flaw in his argument. Self-injury by definition is the opposite of safe. Clean needle programs are invoked, though Sullivan does admit others “note that it encourages drug use, it sends a mixed message and it fails to get people off drugs. Whether it is cost-effective and its validity as an appropriate treatment have also been questioned.”

“Where the risks of serious injury are low limitations on basic freedoms are more difficult to justify.” This is easy to write, but tell it to a mother whose teenage daughter sneaks off to slice herself open. It’s doubtful the mother will love the “freedom to cut” argument.

The argument Sullivan relies on most is that stopping a person from self-injury removes this person’s way of “coping.” But then this person also has to cope with the cutting, and from the stress of hiding this (as is usual) from others, and from other worries associated with the cutting. And then it does not follow that self-injury is the lone way a person can cope with life.